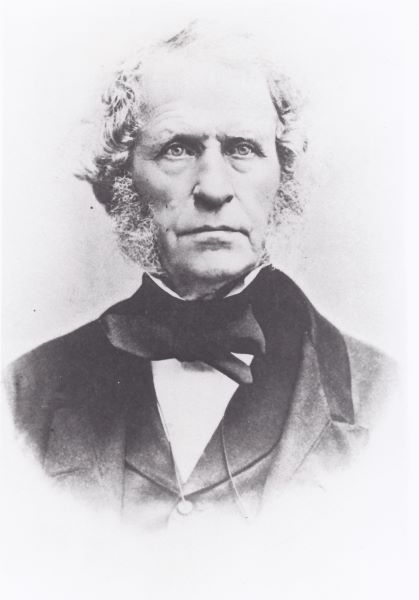

Walter Crum

Walter Crum

Walter Crum (1796-1867) was an eminent scientist and industrialist in the field of textiles, whose family was responsible for the growth of Thornliebank through its calico printworks. He was described as having done “more than any other manufacturer of his time to elevate a trade, which had hitherto been practised empirically, into something of a science, based upon exact principles” (1). In addition, he was a man of admired character and public spirit.

Early Life

The Crum family’s social and political standing had been growing ever since John Crum set up his sons, John and Alexander (Walter’s father), in the calico printing business at the end of the eighteenth century. The Crums were Liberal in their politics, being friends of the Maxwells of Pollok (Sir John Maxwell was the Liberal MP for Paisley), and being Glasgow neighbours of David Dale, of New Lanark renown.

Walter received a traditional Liberal education, attending a private school and then Glasgow University. After university, he spent two years studying and working with James Thomson, the accomplished chemist and pioneer of scientific industry, at Clitheroe in Lancashire. Thereafter he went abroad to attend to family business interests in Smyrna, spending two years travelling around Asia Minor and Turkey, as well as advancing his studies in France and Germany. This afforded him a knowledge of European languages and of prominent scientists, as he met Alexander von Humboldt, Jean-Baptiste Dumas and Justus von Liebig.

At twenty-two he enrolled in chemistry classes at Glasgow University under Thomas Thomson, Regius Professor of Chemistry. Crum’s notebooks describe experiments carried out in what is now acknowledged as the first university laboratory class in the country.

This period of study culminated in the publication of Walter’s first scientific paper: Indigo, published in 1823 in the Annals of Philosophy. It attracted much attention and praise, and helped to establish him as a scientist.

A Man of Science

At Thornliebank, Crum was able to put his theories into practice in the business of dyeing and calico printing. He had a laboratory in the printworks, and continued his research throughout his life. Papers such as Primitive Colours and Dyeing of the Cotton Fibre obviously related to textiles, but he also wrote on more diverse subjects, including the Stalactites of Derbyshire and The Origin and Nature of the Potato Disease. His works were translated and published in France and Germany, spreading his repute abroad.

He was a long-standing President of the Philosophical Society of Glasgow and assisted in the development of both the Mechanics’ Institute of Glasgow and Anderson’s University (now the University of Strathclyde). In 1844 he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of London. He was also secretary to the Select Association of Master Calico-Printers, an organisation which we know little about.

Success in business

Walter spared no expense to have the best machinery and to turn out the highest quality of product at Thornliebank. He set about improving the works by increasing the water purity and flow by raising the dam below Spiersbridge, and by creating the loch which led water from the Auldhouse Burn into reservoirs in the printworks. He also tried to improve conditions for his workforce, by, for example, inventing a continuous ager for the room in which cloth was steamed, thus reducing the intense heat that workers had to endure.

The growing importance and social standing of industrialists like the Crums was recognised when, in 1859, the printworks was visited by the then Prince of Wales, Prince Albert Edward. The Prince was apparently very impressed, and the Crums were guests of honour at the subsequent Royal dinner held at Pollok House with Sir John Maxwell.

Public Spirit

The Crums were known as being ‘enlightened employers’ for their time, and Walter had a keen interest in the local community and in public affairs. He was responsible for opening Thornliebank’s first school, and census returns from the mid nineteenth century show that a high proportion of children under twelve in Thornliebank were pupils. He allowed local Methodist worshippers to use the old Reading Room free of rent until their church could be built, and also supported the building of a secession church at Spiersbridge. Villagers who wanted to set up a co-operative association were promised his support, and he provided them with premises at 12 Main Street to use as a shop.

Private Life

Walter married in 1826. As the business prospered, he bought Rouken Glen estate and mansion house about 1857, where he planned and planted the famous walled gardens. His eldest daughter married William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, while his son, Alexander, continued running the printworks in the same way as his father, expanding and improving. Alexander had many houses built in the village as well as the village hall, public baths, park and library. He was also involved in the building of Thornliebank School in 1875.

It was said that Walter Crum never suffered from illness during his lifetime, but his health began to falter in 1867. When he died later that year in Thornliebank, he was described as “a remarkable man of unbending rectitude and love of truth, with a decision of character, public spirit and perseverance in whatever he undertook” (2).

References

(1) MacLehose, James, Walter Crum, Memoirs and portraits of one hundred Glasgow men, 1886, p94

(2) Crum, F. M., Alexander Crum of Thornliebank 1828-1893: a memoir, 1954, p5

Further Reading

Crum, F. M., Alexander Crum of Thornliebank 1828-1893: a memoir, Macneur & Bryden, Helensburgh, 1954

David Duff, The forgotten pioneer [Thomas Thomson], in Chemistry in Britain, May 1997, Vol 33(5), pp. 46-48

Isaacs, Yvonne, The ‘model village’: nineteenth century Thornliebank and the influence of the Crum family

Crum’s Land: A history of Thornliebank, Eastwood District Libraries, 1988

Thornliebank School 1877-1977 centenary brochure