Alexander, 10th Earl of Eglinton, (1723-1769)

Alexander, 10th Earl of Eglinton, (1723-1769)

A hereditary member of the nobility and a politician, Alexander 10th Earl of Eglinton (1723-1769) is best remembered locally as a great agricultural improver, and it was he who designed the planned village of Eaglesham.

We now look at Eaglesham as a wonderfully unspoilt example of the 18th century phenomenon, that of the planned village; it was however, at the time of its creation, seen as modern and forward thinking.

Alexander, 10th Earl of Eglinton was born 10 February 1723, son of Alexander Montgomerie, 9th Earl of Eglinton and Susanna Kennedy. He was educated at Winchester College in Hampshire.

He succeeded to the Earldom on 18 February 1729. In addition to his hereditary titles, Alexander held various public offices: he was Governor of Dunbarton Castle between 1759 and 1761, Lord of the Bedchamber between 1760 and 1767 and was a Representative Peer [Scotland] between 1761 and 1769.

However, his great interest seems to have been in agricultural improvement and he spent much of his time and money developing his estates (his main estate being in Ayrshire) and introducing farmers to new ideas and techniques, which he gathered from England, other parts of Scotland and abroad. He also instituted an agricultural society and presided over it for many years.

One report of the time paints a bleak picture of agricultural methods. It describes Ayrshire as having few practicable roads, ditches and fences were few and in bad condition and the land was overrun with weeds and rushes. As for the farm houses, they were described as “mere hovels, having an open hearth or fireplace in the middle, the dunghill at the door, the cattle starving and the people wretched.” (1) The Earl oversaw the management and improvement of his estate himself, and was said to travel and examine every part of his estates as well as personally “arranging the divisions and marches of the farms with all the details of their sub-divisions, roads and ditches, fences and plantations.” He also brought men to his estates who were proponents of these new ideas. For example, he brought Mr. Wright from Orminston in East Lothian (another planned village) to help him introduce new methods.

The level of interest that Alexander had in agricultural matters is demonstrated in a letter he wrote to his brother prior to a duel. After the serious business of giving instructions in the event of his death, he ends the letter with “Don’t neglect horse howing if you love Scotland”. (2) This alludes to the cleaning of drilled turnips which the Earl was anxious should be done by horse drawn scrapers rather than by hand hoeing.

The planned village

Up until the 18th century, there were few villages in Scotland. Patterns of rural settlement were loosely organised around fermtouns; each one consisting of a small cluster of tenants who worked their land together. Settlements which included a church, were known as ‘kirktouns’ and those including mills ‘milltouns’. Before 1769, the parish of Eaglesham consisted of a kirktoun with about 25 houses, acting as a focal point for the 126 fermtouns surrounding it.

The period of the 18th century and early 19th century became known as the Age of Improvement. Many landowners, like the Earl of Eglinton, were keen to institute new methods of farming and replace the old patterns of settlement with something much more organised and productive.

In rural areas, the old fermtouns were swept away and replaced by larger, enclosed, single-tenanted farms. Landowners planned and built new villages which were much more regular in their layout. The new system of farming, combined with improvements in agricultural methods, resulted in a higher yield but also created a surplus of agricultural workers. A planned village could absorb some of this excess produce and labour.

Eaglesham

Alexander 10th Earl of Eglinton saw Eaglesham as an ideal location for such a planned village. As a kirktoun, it would already be a focus for the scattered communities in the area. Since 1672 it had had the right to hold a weekly market and annual fair, and therefore would have established roads and routes to and from local areas and beyond.

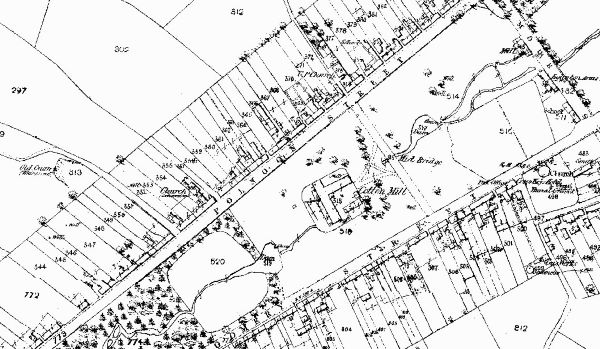

From 1769, the old kirktoun was cleared and the new village began to grow. Alexander planned his new village on very clean lines, in a shape resembling a letter ‘A’. Two roads, North Street and South Street, formed the long sides of the letter, with Mid Road connecting them in the middle. This shape can be seen clearly in the c.1856 map below. The land was sectioned into single and double tacks and let on 900 year leases. The tenants were obliged to build the first house on their tack within 5 years or else forfeit the land. To assist them in this, the original tacksmen were given permission to quarry stone and were given sand from the Earl’s estate.

In between the two roads lay the common ground, which became known as ‘The Orry’ The tacksmen were allowed to use the burn running down its centre for washing and its green for bleaching and it was intended as a place of beauty for the common good.

The Earl’s Legacy

The 10th Earl died a violent death, aged only 46, before his planned village was completed. He was shot dead on his Ayrshire Estate, during a confrontation with excise officer Mungo Campbell, on October 19th 1796.

However, his brother Archiebald, 11th Earl of Eglinton, carried on his work by finishing the planned village and instituting new improvements of his own.

Although the planned village movement came about as a result of agricultural improvements, the 18th and 19th centuries also saw the industrial revolution take hold and the rise of the textile industry in the area. This actually began to draw people away from rural areas to the towns to gain employment in the mills and factories that were springing up. Probably to counteract this, the 11th Earl encouraged the building of a cotton mill in the village and this, as well as hand weaving, provided employment to people and encouraged the growth of the village during this period.

References

(1) Col. Fullarton’s Report, 1793 p9-11 from Fraser, William, Memorials of the Montgomeries, 1859 p121

(2) Fraser, William, Memorials of the Montgomeries, 1859 p342

Further Reading

A planned village: a history of Eaglesham, Eastwood District Libraries, 1988

Brown, Christina Robertson, Rural Eaglesham, Glasgow: William Maclellan, 1966

Deighton, Jane Scott, Eaglesham: an earl’s creation, London: Johnson, 1974

Fraser, William, Memorials of the Montgomeries, Edinburgh, 1859