History of Thornliebank

Read on to discover the origins of Thornliebank

The story of Thornliebank is synonymous with the story of the textile industry and in particular with the arrival of the Crum family and the growth of the Thornliebank Printworks.

Early History

Thornliebank does not appear on any maps until 1795, when it is shown as a small cluster of buildings with its name written in the form of ‘Thornybank’. The area the village grew to occupy was part of the barony of Eastwood, owned for a long time by the Earls of Eglinton.

Beginnings of the Village

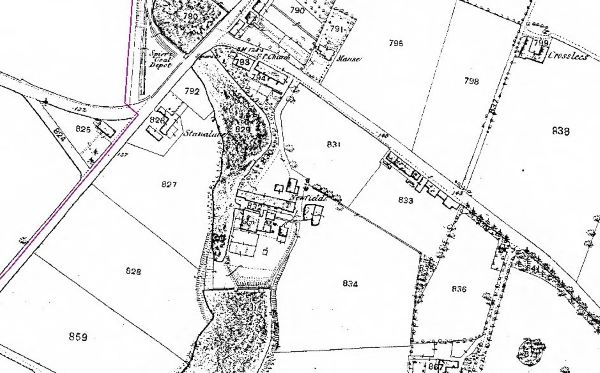

The story of the village of Thornliebank starts with the ambitions of one Robert Osburn, a linen printer. In 1778, Robert took out a lease of 12 acres from Archibald, Earl of Eglinton, although not on the spot the village now occupies but “lying along the Auldhouse burn on the north side of the Great Road leading from Pollokshaws to Stewarton” (1) Robert established a printfield here called Newfield (shown on the map below c.1856) and it seems that he enjoyed enough success to lease further adjacent lands from the Maxwells of Pollok. His ambition was to expand the works. However this appears to have been his undoing as in 1789 he was declared bankrupt and forced to give them up.

Thornliebank and the Crums

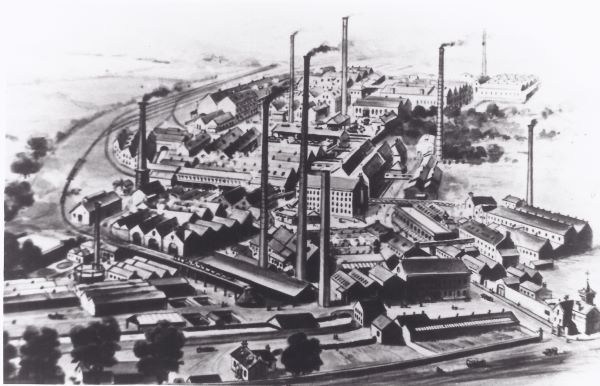

John Crum, who already had a thriving business at the Gallowgate in Glasgow, saw a good business opportunity and bought over Osburn’s holdings at Thornliebank and Pollokshaws. He purchased it, not for himself, but for sons Alexander and James who he had previously set up in a printing and manufacturing business in Selkrig’s Closs, also in the Gallowgate. Alexander and James were looking to expand and the Thornliebank location, with its access to the Auldhouse Burn, seemed ideal. For a time, the brothers continued the operation at Newfield but expanded the business northwards to the site of the present day Spiersbridge Business Park (below)

In the beginning, all aspects of textile work was carried out at Thornliebank. Cotton was manufactured on hand looms and power looms, the works had its own cotton mill and cloth was bleached, printed and finished on site. Under Walter Crum (1796-1867) the business stopped manufacturing cotton and concentrated on bleaching, dying (including turkey red), finishing and beetling. Goods from the works were sold all over the world and it was said that in Thornliebank “here were produced the finest textiles in all Europe.” (2)

The Crums retained ownership and management of the works until 1899. Of the two brothers only Alexander had children and so it passed to his sons John, Walter, Humphrey and James. Eventually Humphrey and James left and Walter was left solely in charge. When Walter died his son Alexander (1828 – 1893) took over the management of the business. After Alexander’s death the business declined and was taken over by the Calico Printers Association in 1899. The works finally closed on Christmas Eve 1929, completely changing the identity of the village forever.

Development of the Village

By the time the Crums bought over the works, a small village was beginning to develop. It consisted of only a little row of workers cottages and a few additional buildings but by 1845, the population had boomed to 1366 and by 1867 when Alexander Crum took over, there were around 450 – 500 houses in the village. It was completely centred around the works and in the Second Statistical Account written in 1836 we learn “The village of Thornliebank is situated a mile to the south-west of Pollokshaws, the whole of which, with the exception of two or three small houses, belongs to Messrs Crum, and is almost wholly occupied by persons in their employment.” (3)

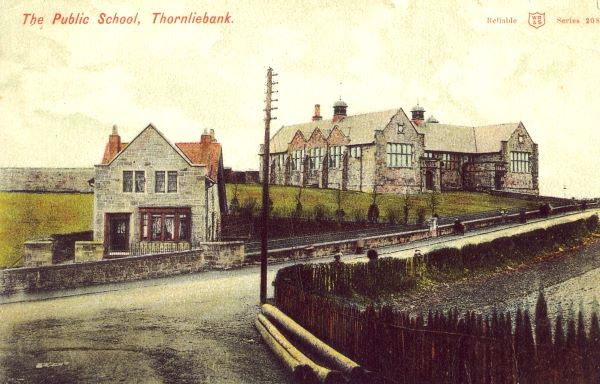

By the standards of the time, Alexander Crum was an enlightened employer. He built rows of red brick houses for his workers in 1870, for example, Franklin Terrace and Campsie Terrace, and these were said to be of high quality. He improved sanitation by installing a sewage system in the village as well as putting gas and water into the new houses. As well as improving village housing, Alexander seems to have cared about the social welfare of his workers as he was instrumental in establishing the village club and other leisure facilities, was involved in the building of Thornliebank School in 1875 and he and his father financially supported Thornliebank Parish Church and other local causes. In the words of his brother-in-law, Lord Kelvin, “Alexander never tired of doing good. He laboured incessantly – They had only to look round the village and the works.”

From all accounts, Alexander was seen as the village’s main benefactor, so much so that when he died, the Crum Library, formally opened on 5th January, 1897 and designed by the Scottish architect Sir Rowand Anderson, was built from funds raised by the village to commemorate him.

The village continued to grow and thrive throughout the second half of the 19th century and into the 20th century. Transport links, which became vitally important to the long term survival of the new industrial towns and villages, improved when Thornliebank Railway Station opened in 1881. In 1908 Glasgow Tramways extended its route to the popular new public park at Rouken Glen via the village. In 1910 Paisley District Tramways opened a second route to Rouken Glen via Spiersbridge and by 1922 there were several private bus companies running services.

The growth of the village was reflected by the need for a new church and Thornliebank Parish Church opened in 1855. The Catholic population in the village had taken root in the mid 19th century with the immigration from Ireland of those seeking work in the burgeoning textile industry. They had to wait a bit longer for a place of worship but by 1942 the congregation of St. Vincent de Paul was meeting in a temporary building, until the opening of the current church in 1960.

As working conditions slowly improved, locals started to enjoy spending their increased leisure time in a variety of pursuits and amongst other things, sporting, drama and music clubs were established. There was even a local football team, Thornliebank FC, who reached the final of the Scottish Cup in 1880.

Life at the works

Although, especially under Alexander, the Crums were seen as enlightened employers, it did not mean life was always easy for the work force.

The owners of industrial villages, such as at Thornliebank, would completely dominate every aspect of an employee’s life. Accommodation was tied to employment so if a worker had to leave or was dismissed, then it also meant finding somewhere else to live. Truck systems were operated, whereby workers would be paid in tokens or in kind, meaning that these ‘wages’ could only be exchanged for food and supplies provided by the employer at whatever cost they saw fit. In Thornliebank this led to a bread riot in 1848.

The Factory Act of 1833, which limited young people’s working hours to 12 hours per day, excluded bleaching and dyeing industries and so even as late as 1860, children from the age of 7 and upwards would work from 11 – 18 hours a day. In Thornliebank there were reports of children being carried home on their parent’s backs fast asleep due to exhaustion.

In Walter Crum’s favour, in 1861, he did support villagers by providing premises for a Co-operative store. Alexander encouraged them to expand by renting them a site on Main Street and a two-storey building was erected with a coal department and dairy added. In 1905, the Co-operative society built a larger three-storey tenement which survives as the present day Unitas Buildings.

The Twentieth Century

Although the final closure of the printworks in 1929 brought an end to Thornliebank’s core identity as an industrial village, it has continued to grow as a residential area in much the same way as other places in East Renfrewshire. In the 1930s, 630 private houses were built by Mactaggart & Mickel in the Orchard Park Estate and the Woodfarm Housing Estate was built by the local authority in the 1950s. In the 1970s some of the Crum’s earlier buildings, such as the properties on North Park and Campsie Terraces, were demolished, having become outdated and run down. Today the village has quite a mix of housing from private to public housing and from large villas and sandstone houses to tenements and flats both traditional and modern in style.

Thornliebank School which was built to accommodate the Education Act of 1872, which required all young people between 5 and 13 to be in full time education, still survives on the same site. A local high school, Woodfarm, was added in 1962. It started life as a junior secondary with pupils being moved on to Eastwood High School (at its old Seres Road location) and became a six year comprehensive in August 1978. In 1984, St. Ninian’s became the local Catholic High School, saving pupils the long journey to Paisley for their education.

The old site of the printworks which had been the lifeblood of the village for so long, lay derelict for several decades after its closure but now has a new function as the Speirsbridge Business Park which houses councils offices and as well as a wide range of local businesses.

References:

(1) 1874, The Crums of Thornliebank, Glasgow Herald, 23 Sep.

(2) Crum’s Land: A History of Thornliebank, Eastwood District Libraries, 1988, p.4

(3) Logan, Rev. George, Eastwood Parish, Seconds Statistical Account, 1836

Further Reading

Crum’s Land: A History of Thornliebank, Eastwood District Libraries, 1988

F.M.C, Alexander Crum of Thornliebank (1828 – 1893): A Memoir, Helensburgh, 1954

Devine, Maud, Old Thornliebank, Stenlake, 2005

Welsh, Thomas C., Eastwood District History and Heritage, Eastwood District Libraries, 1989